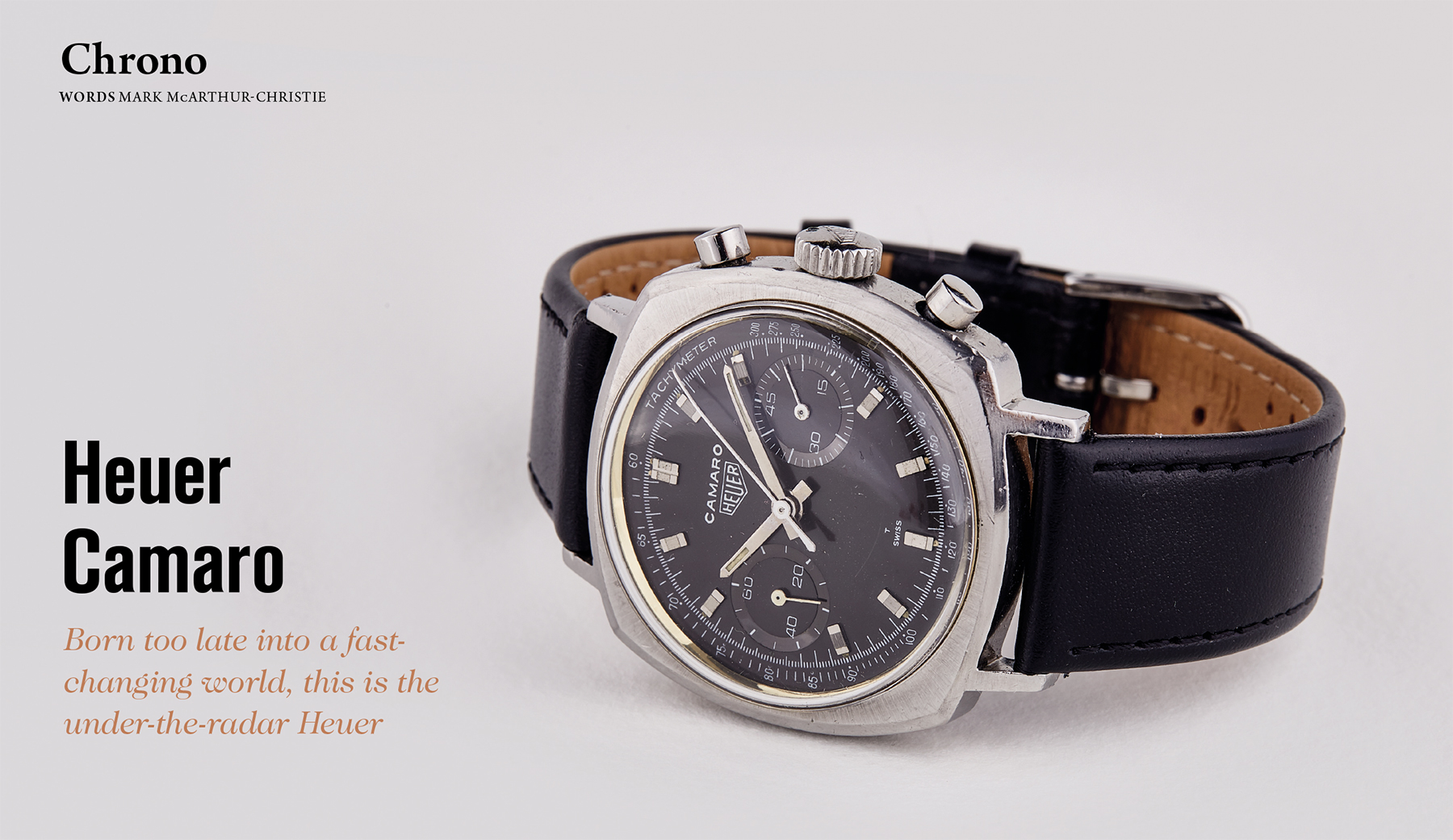

JAMES LEIGHTON is clearly a man of taste and discernment. Not only does he read Octane’s Chrono pages (the best bit, let’s face it) and own a Heuer Camaro, but he emailed to ask if we could write something about his watch. It’s a good call: Monacos, Carreras and Autavias are ten a penny (price not adjusted for inflation) but when did you last see a Camaro?

It’s a watch that, right from the outset, got an undeserved bum deal. Sandwiched between the stalwart Carrera and the groovy new Monaco, only a few thousand examples were made before Heuer dropped the Camaro. The watch itself is a belter; the problem was timing.

In 1967, as Heuer was adding the final touches to the Camaro prior to its launch the following year, the corporate eye was distracted by a bigger prize. Although chronographs were nothing new, there was, as Jack Heuer put it, ‘a significant gap in watchmaking technology’. Until the end of the 1960s, one still had to wind one’s own chronograph. There were plenty of chronos and even more automatic watches but no-one had managed to put the two together commercially in an automatic chronograph.

To make a self-winding watch (being pernickety, it’s wound by the wearer’s movement and gravity) one needs a moving mass. Watchmakers from Perrelet in the 18th Century on had tried everything from bumperand-spring winders to oscillating weights. The issue was finding space in the watchcase – and in the movement itself – for all the cams, levers and gears a chronograph needs, as well as a winding weight and its associated gubbins.

There were three groups of watchmakers vying to be first across the line in the 1960s. An alliance between Heuer, Buren-Hamilton, Breitling and Dubois-Depraz (the Chronomatic) were up against Zenith and its El Primero while, unbeknown to either, Seiko was working on its cal. 6139. Once Heuer launched the new automatic movement in 1969 and put it in watches such as the cool new square-cased McQueen-favourite Monaco, the poor Camaro with its keep-fit winding system was simply old hat. It lasted until just 1972 before Heuer pulled the plug.

Despite its short life, there are enough varieties of Camaro to keep even the most obsessive collector happily rummaging. The 37mm cushion case – halfway between the Monaco and the Autavia – is a constant, but even in that there were material variations. You could choose solid yellow gold (good luck tracking one down), gold plate or stainless steel (sadly no PVD, more’s the pity).

Heuer used three movements for the watch: the faithful Valjoux cal. 72, the cal. 92 and the cal. 773X range, evolved from the Venus 188. It gives you an idea of just how nuts Watchworld is when you think one of those – the Valjoux cal. 72 – also pops up in the pre-806 Breitling Navitimer and the Rolex Daytona. In the B’ling, you’d be looking at anywhere north of £15,000 for an APOA model. For the Daytona with a cal. 72? A kidney or two? Your immortal soul? In the Camaro, around £4500 for a tripleregister ref. 7220 NT. Now tell me the Camaro isn’t the bargain of the decade.

Then there are the dial variations. You’ll see everything from that same wonderful, clear Singer silver eggshell on the ref. 7743 that’s shared with the Carrera through blues, blacks and whites. Most Camaros came with a double register chronograph, running seconds at 9 o’clock and a minute counter at 3 and a 1 / 5- second chronograph central seconds. But there were three-subdial variants, too, the 7220 and 7228 as well as the 73643. The third dial carried a 12-hour counter.

No matter which dial you choose, you get to enjoy Heuer’s obsession with clarity. In fact, you can see its evolution from the classical light/dark contrasts between dials and hands of the early watches through to the use of colour on the later models. For example, on the 73643NT you’ll see each of the three chrono hands in orange, marking them out from the standard time hands in white or silver. Depending on the dial, the bezel’s tachymeter might be picked out in orange, too.

There were also ‘specials’ – when the 1978 Canadian GP resulted in a podium of Villeneuve, Scheckter and Reutemann, sponsor Champion sparkplugs had Heuer produce a ref. 73443 Camaro with its logo on the dial.

Despite the ties with racing, Heuer never seemed to know quite where to pitch the Camaro. Ads variously offered it as a yachting watch, or as just the ticket for timing Polaroid exposures, long-distance calls (remember those?) and time left on parking meters.

In 1972, the firm quietly pulled the plug on the Camaro. The poor thing never had a chance. Why did Heuer not just update the Camaro with the new Chronomatic movement? Simple – the case wasn’t big enough. One wonders what its fate might have been had McQueen decided to buckle a Camaro instead of a Monaco to his wrist on the set of Le Mans.

Words by Mark McArthur-Christie, for Octane Magazine